Stress in Yimas is predictable. Namely, it assigns primary stress to the first syllable of the word, and secondary stress to the third syllable if the word consists of more than three syllables. The rules are stated below:

However, an exception occurs when the first vowel of the word is epenthetic. In this case, the epenthetic vowel is not stressed, and primary stress moves to the second vowel in the word. Furthermore, these forms never bear secondary stress.

Moreover, there is an additional exception when the first two vowels of a word are epenthetic: the Primary Stress Rule (1) takes place (the first syllable receives primary stress). This is because one of the first two vowels must bear primary stress.

When affixation occurs, we can see that the addition of a morpheme affects the assignment of stress. An affix always receives a particular stress assignment—it can either be stressed or unstressed. The following example outlines what occurs when a morpheme that always receives secondary stress is added:

In order to create the dual (DL) and plural (PL) forms of the word kɨpáŋ “leg”, the morphemes /-kɨl/ and /-kɨ/ are suffixed, respectively. These morphemes always receive secondary stress; thus, in kɨpáŋkɨ̀l and kɨpáŋkɨ̀, primary and secondary stress are in adjacent syllables. According to the Epenthesis Stress Rule (3) outlined above, this should not happen—only primary stress should exist. Moreover, with the consideration of the Primary and Secondary Stress Rules (1) and (2), there is evidence that in Yimas it is more desirable that stress alternate syllables. Because the final form of the word violates rules (1), (2), and (3), one can conclude that stress assignment does not occur all at once; it in fact in cycles.

Example (5) shows stress application if /kpaŋkɨl/ were monomorphemic. The Epenthesis Stress Rule (3) would generate primary stress on the second syllable because the first vowel is epenthesized. Consequently, the incorrect form *kɨpáŋkɨl is produced.

In Example (6), we see that stress is not applied to the entire word as a whole because this form truly consists of two morphemes, corresponding to two different cycles. First, the Epenthesis Stress Rule (3) applies to the root /kpaŋ/ in Cycle 1, resulting in kɨpáŋ. Then in Cycle 2, the suffix /-kɨl/ is added to the root. This morpheme always receives secondary stress, regardless of position, resulting in the correct form: kɨpáŋkɨ̀l.

Lastly, an example of the addition of a type of morpheme that is always unstressed is presented below:

Pronominal prefixes in Yimas are normally unstressed, so the stress rules (1), (2), (3), and (4) are applied to the root as if there were no prefixal syllables. This is also evidence of cycles.

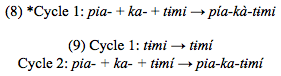

Example (8) shows stress application if there were only one cycle. Primary and Secondary Stress Rules (1) and (2) assign stress on the first and third vowel. This produces the incorrect form *pía-kà-tɨmi.

Example (9) shows stress application in two cycles. First, stress is applied to the verbal root. Because a vowel is epenthesized, Epenthesis Stress Rule (3) generates tɨmí initially. Next, the two pronominal prefixes are added in Cycle 2. They never receive stress, so no stress is added in this cycle, and the form produced in Cycle 1 is preserved.

Foley, W. (1991). Phonology. In The Yimas Language of New Guinea (pp. 75-80). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.