Introduction

The Maori language is spoken, for the most part, in the North Island of New Zealand. To be more specific, it is mainly spoken in the far North, Central, and Eastern regions of the North Island where the Maori population is abundant. Although up for debate, it is generally agreed that there are 3 main dialect divisions in the language. The dialects, however, are thought to be universally understood across the different dialects. A 2013 New Zealand Statistics Survey found that there are around 50,000 Maori adults remaining who can speak the language at a high level. This amounts to about 11% of the population, with the majority of the truly fluent speakers aged over 65. An interesting morphological phenomena in the Maori language is reduplication, which is a process where all or part of a word is repeated in order to serve some grammatical or semantic function.

Infixed Reduplication

There are three main ways that reduplication functions in Maori, the first of which is to signify pluralism using infixed reduplication. Often times, inflixed reduplication surfaces by way of lengthening a vowel in the centre of the word, as only one segment is reduplicated. This is seen frequently in the use of infixation in nouns.

Table 1.1

| Base Form | Base Gloss | Reduplicated Form | Reduplicated Gloss |

| tangata | “man” | ta:ngata | “men” |

| wahine | “woman” | wa:hine | “women” |

| tupuna | “ancestor” | tu:puna | “ancestors” |

| tuakana | “older sibling” | tua:kana | “older siblings” |

| tuahine | “sister” | tua:hine | “sisters” |

The elongation of certain vowels in the words shown in Table 1.1 is a result of the reduplication of a single internal segment. Notice how the placement of the lengthening occurs in the first three words versus the last two. We will discuss later in the section why the lengthening lies on the /a/ in both of the final two examples. The word structure trees below show how reduplication appears in the two contexts provided; namely, when there is a CVC structure, or a CVVC structure.

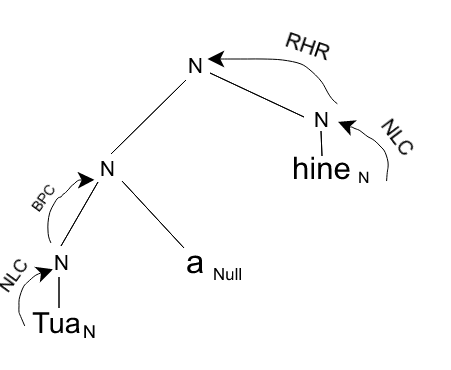

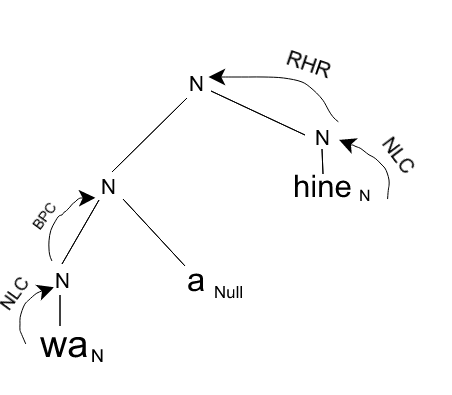

Tree 1a

Tree 1b

Although the context of the words is different, there are common word structure patterns in both of the trees. You may notice that the reduplicated segment, which is /a/ in both of the above trees, is not involved in percolation, seeing as it has null category. This attests to the fact that in nouns, infixed reduplication changes nothing about the meaning and only signifies a change in number. BPC takes over where the null morpheme exists, and from there NLC and RHR allow for percolation of the nominal category. Seeing as the same type of word structure trees occur in both CVC and CVVC contexts, there is no clarification offered by the trees as to why the lengthening in both “sisters” and “older siblings” lies on the /a/ and not the /u/.

The data on infixed reduplication in nouns above in Table 1.1 and Trees 1a and 1b allow for only the observation that reduplication occurs only within the initial part of the word, but it explains nothing of why it occurs where it does. In fact, the only way to have the answer to this question is to also have abundant amounts of data. It turns out that in Maori, the targeted location for infixed reduplication is the antepenultimate vowel of a word. This means that regardless of where the root morpheme lies within a word, or if the structure is CVC or CVVC, the second to last vowel is the one which will be elongated with infixed reduplication. This approach is seen now as an older method of analyzing Maori reduplication, but one that still holds true of noun pluralization. In Table 1.1 above, the antepenultimate approach certainly holds true, which is especially relevant in explaining the examples of reduplication shown where there is a CVVC structure. The antepenultimate vowel reduplication seen above is the most commonly seen example of infixed reduplication in Maori. It is also the most common way to show pluralism in the language.

This is not to say, however, that reduplication is the only way to show pluralism. Table 1.2 shows a special case for the word tamaiti, or “child”.

Table 1.2

| Base Form | Singular Gloss | Plural Form | Plural Gloss |

| tamaiti | “child” | tamariki | “children” |

Although “child” is both a noun and relational term, as are all of the examples in Table 1.1, there is no pattern of reduplication shown in its Maori translation. This may seem odd, as based on the previous examples, one might expect the plural output of tamaiti to become tama:iti. This difference in plural representation can be explained further by breaking down the actual morphemes in the Maori word. Although in English the word “child” is simply one morpheme, Maori treats it as multiple morphemes. In Maori, the same word “child” can be further broken down into multiple morphemes; namely, “tama” which also is present in the meaning for the word “son”, and two other adjectival morphemes which give the meaning “small”. This means that tamaiti is technically a compound, and therefore it will not be pluralized as a simple noun would.

Partial Reduplication

Maori also uses reduplication as a way to extend the meaning of a word. In some cases, Maori employs partial reduplication of a morpheme and in other cases it uses full reduplication. Partial reduplication often will slightly change the meaning of the word while full reduplication will further extend the meaning. An example of this would be the morpheme paki which means “to pat”. Using partial reduplication, the new word is papaki which means “to slap or clap once”. When you fully reduplicate the morpheme paki to pakipaki the new word meaning is “applaud”.

Reduplication also occurs partially to convey de-emphasis or emphasis. This is the case for the morpheme whero “red”. The new word is whewhero “reddish”. Other adjectives such as pai “good” are partially reduplicated to papai which now has the meaning of “very good”. Partial reduplication can also indicate a single intense action in verbs or indicate reciprocity. As we saw earlier in paki “to pat”, the partial reduplication papaki means “to slap or pat once”. Another example of this is the Maori word kimo “wink”. When you partially reduplicate kimo to kikimo the meaning changes to “shut the eyes”. An example of reciprocity can been seen in the morpheme piri “cling”, when partially reduplicated the new word is pipiri “cling together”. Looking at the data, it appears that partial reduplication in adjectives works to emphasize or de-emphasize the meaning and in verbs it works to either show reciprocity or to intensify an action.

Table 2.1

| Base Form | Base Gloss | Reduplication Form | Reduplication Gloss |

| Paki | “To pat” | Papaki | “To slap or clap once” |

| Kimo | “To blink” | Kikimo | “Shut the eyes” |

| Whero | “Red” | Whewhero | “Reddish” |

| Pango | “Black” | Papango | “Blackish” |

| Piri | “Cling” | Pipiri | “Cling together” |

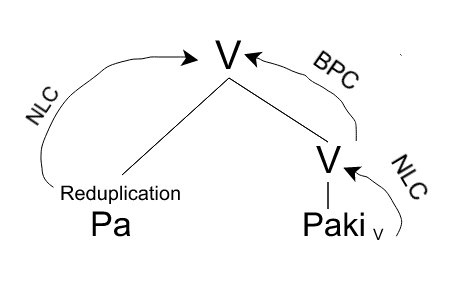

Tree 2a

Full Reduplication

Full reduplication also occurs in Maori as a methodology for extending the meaning of the word; generally when reduplication occurs, it intensifies the meaning of a verb. However, in some specific cases it diminishes the meaning as will be discussed below. Quite often it is seen in verb derivation as a way of signifying a continued or continuing action, or an action that occurs frequently.

In the Maori language, word structure is governed by mora, which can either be V or CV. Full reduplication occurs most frequently in bimoraic stems where the resultant syllabic pattern is σ1σ2σ1σ2; the other reduplication patterns in bimoraic and trimoraic stems most frequently result in partial reduplication.

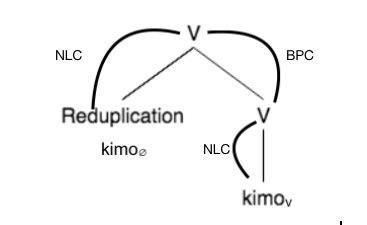

Tree 3a

In our tree diagram you see that there is both NLC stemming from the reduplicated part of the word because it adds more meaning than could be garnered just from the original word itself.

- Bimoraic reduplication:

a. First mora: µ1µ1µ2, ex: papaki (to slap/clap once)

b. Both mora: µ1µ2µ1µ2, ex: pakipaki (to applaud)

c. Final mora: µ1µ2µ2, ex: anganga (respect), from anga (to face)

2.Trimoraic reduplication:

a. First mora: µ1µ1µ2µ3, ex: hoata > hohoata (colourless)

b. First two mora: µ1µ1µ2µ2µ3, ex: taweke > *tataweweke > ta:weweke (slow)

c. First two mora: µ1µ2µ1µ2µ3, ex: takai > takatakai (wind round and round)

d. All three mora: µ1µ1µ2µ3µ2µ3, ex: matuku > *mamatukutuku > ma:tukutuku (Reef Heron)

It is of importance to note that the forms in 2b and 2d are not that which you would expect. Ray Harlow (1991) notes that this is most likely due to a process called C-deletion which would require consonants to delete in specific conditions which would result in a long vowel.

You will find both “right-anchoring” and “left-anchoring” stems in trimoraic reduplication of types 2c and 2d; given the string “matuku” the stem could either be “matu” or “tuku”, but we see that the Right-Anchor stem is ultimately the pattern that occurs for this word, whereas the Left-Anchor stem is the appropriate pattern for the stem “takai”. Reduplication of Left-Anchor stems is more common in Maori as it occurs in verbs, whereas reduplication of Right-Anchor stems occurs in nouns to more specifically identify an item. For example, in 2d, “matuku” means heron, and the reduplicated version more specifically denotes the Reef Heron. Regardless of the subtype of reduplication we see, the reduplication process works by attaching the reduplicated segment to the left of the anchor.

There is also another type of bimoraic reduplication that initially represents itself as full reduplication and then undergoes a C-deletion step due to the phonological constraints of the language. This occurs when segmentation of the form does not necessarily produce two stems.

3. Bimoraic “full” reduplication/C-deletion

a. kuku (draw up), ku:kuku (tie together)

b. rere (leave), re:rere (run)

Because there is no way to stipulate that words produced by this type of reduplication must result in a long vowel, there must alternatively be a No-Long-Vowel Rule that prevents a long vowel from occurring in the other forms outlined in 1 and 2.

Bimoraic reduplication of type 1b, trimoraic 2d, and the bimoraic C-deletion type 3 are all considered to be full reduplication and generally intensify the meaning conveyed by the original stem. Reduplication in a stative verb, however, will diminish the intensity of the meaning.

Table 3.1

| Base Form | Base Gloss | Reduplicated Form | Reduplicated Gloss |

| Mate | “Die” | Matemate | “Die in numbers” |

| Kimo | “Wink” | Kimokimo | “Wink frequently, blink” |

| Wera | “Hot” | Werawera | “Warm” |

| Mate (stative) | “Sick” | Matemate | “Sick-ish” |

| Tata | “Near of place or time” | Ta:tata | “Near” |

| Pakaru | “Break” | Pa:karukaru | “Break into pieces” |

Conclusion

We have seen now how three different types of reduplication occur within Maori. Infixed reduplication occurs within nouns, where it affects the antepenultimate vowel regardless of other context or factors. Reduplicated segments here trigger BPC, as they have null category and do not change the root meaning of the word at all. Partial reduplication can occur in more contexts than infixed can, and it applies to multiple word categories. Verbs are usually partially reduplicated to show reciprocity or to further intensify the action being formed. Adjectives use partial reduplication to either emphasize or de-emphasize the original meaning. The final type of reduplication is full, where the entire word is repeated. Verbs that are fully reduplicated usually either represent a continuous or frequently performed action, but can also in some cases diminish the meaning.

References

Biggs, B. (2013). Let’s Learn Maori. New York: Auckland University Press.

de Lacy, Paul (1996). Circumscription revisited: an analysis of Maori reduplication, ROA 133.

Harlow, Ray. (1991). “Consonant Dissimilation in Maori,” in Robert Blust (ed.), Currents in Pacific Linguistics: Papers on Austronesian Languages and Ethnolinguistics in Honour of George W. Grace, Pacific Linguistics Series C-117, 117-128, Canberra: The Australian National University.

Harlow, R. (2007). Māori: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Williams, Herbert W. (1971). A Dictionary of the Maori Language. 7th edition. (orig. 1844). Wellington, N.Z.:A.R.Shearer, Government Printer.

¹A “mora”(symbolized as µ) is a unit of measure that determines syllable weight. The number of mora is equivalent to the number parts that syllables are divided into.

²We will define the “anchor” as the part of the stem that gets reduplicated. If the anchor is on the right, we call it right-anchoring and likewise if the anchor is on the left we call it left-anchoring

³A stem will be defined here as the grouping of mora