Introduction

Italian is part of the Indo-European language family, which consists of several hundred related languages and dialects. It is a romance language with approximately 85 million worldwide speakers and is an official native language in several places such as Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City and western Istria.

In this first blog post, we will be talking about compounding in Italian. Most of the Italian compounds we have found are noun compounds with a few being adjective compounds but we were unable to find any verb compounds. This leads us to believe that verb compounds in Italian are very rare if not non-existent. Furthermore, there are several different category combinations that could be used to form Italian compounds. These combinations include (noun + noun), (noun + adjective), (adjective + noun), (verb + noun), (adjective + adjective), (verb + verb), (verb + adverb), (adverb + verb), (adverb + adjective) and (adverb + noun). In order to understand how compounds are formed in Italian, we will focus on compounds with the category combinations (noun + noun), (adjective + adjective), (verb + verb), (verb + noun) and (noun + adjective).

Endo-Centric Compounds

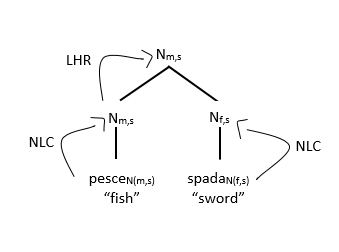

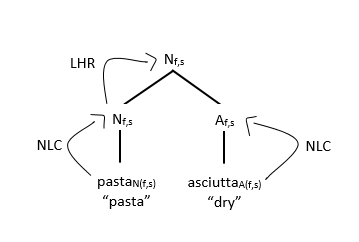

Just like English, the simplest Italian compounds are formed by joining together two roots. Which of these roots is the head of the compound is determined by the category and meaning of the compound as compared to its parts. These types of compounds are endo-centric compounds defined as those which contain a head. This can be seen in examples (1) and (2) below for the compounds (1) pesce spada “sword fish” and (2) pasta asciutta “dry pasta”.

(1)

(2)

Looking at the first example, we can see that the head of the compound pesce spada is the left most morpheme pesce. This is because pesce spada or sword fish is a kind of fish (pesce) rather than a kind of sword (spada). The head of the compound also determines the features of the compound, thus pesce spada, just like pesce, is masculine and singluar. Furthermore, in example (2), pasta asciutta, the head of the compound is also the left-most morpheme because dry pasta is a kind of pasta (pasta) not a kind of dryness (asciutta). We can also see from this second example that the word pasta asciutta is a noun rather than an adjective. This is because the category of the head of the compound percolates up and provides the category for the top most node. For these reasons, we have theorized that Italian is a left-headed language where the category of the left-hand member of a compound determines the category of the whole.

Dvandva Compounds

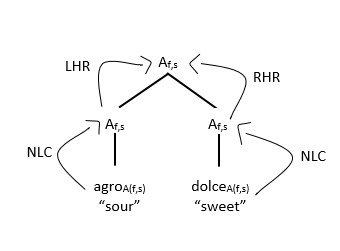

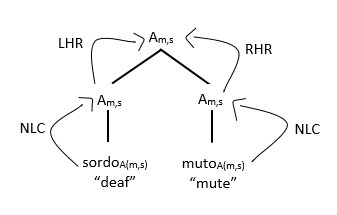

Both of the Italian compounds above are examples of endo-centric compounds but there are also instances of dvandva compounds and exo-centric compounds. Dvandva compounds are those which contain two heads while exo-centric compounds are defined as those whose head is outside of the compound. Examples of dvandva compounds can be seen below with (3) agrodolce “sweet-and-sour” and (4) sordomuto “deaf-mute”.

(3)

(4)

When looking at both of these examples, we come to an interesting realization. We realize that sweet-and-sour is both semantically sweet and sour and that deaf-mute is both semantically deaf and mute. Furthermore, when we look at the categories and features of the compounds, we see that both agro and dolce are feminine, singular adjectives and the compound as a whole is also a feminine, singular adjective and sordo and muto are masculine, singular adjective with the compound being a masculine, singular adjective as well. Thus, we come to the conclusion that these compounds are dvandva compounds with both of the roots being heads. Because both of the roots are heads there is an application of LHR as well as RHR in the trees above.

Exo-Centric Compounds

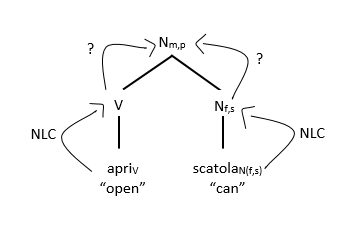

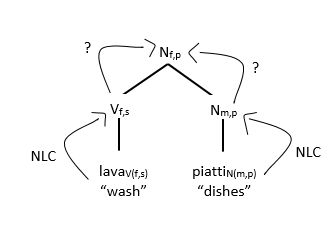

As mentioned before, there are three types of compounds; endo-centric compounds, dvandva compounds and exo-centric compounds. We have already covered endo-centric compounds and dvandva compounds thus this portion of our blog will focus on exo-centic compounds, those which do not contain a head. We will begin by looking at example (5) for apriscatole “can opener” and (6) for lavalpiatti “dishwasher” in which we see a problem arise.

(5)

(6)

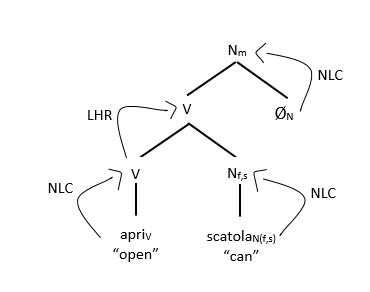

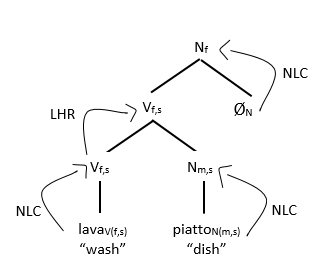

Beginning with (5), when we try to determine the head of apriscatole we find that it is not apri nor is it scatola because a can opener is not a type of opening nor is it a type of can. If we look at the categories at each node of the tree we see that the compound is a noun but apri is a verb so it cannot be the head of the compound. Although scatola is a noun it is a feminine, singular noun while the compound is a masculine, plural noun so scatola cannot be the head of the compound either. Looking at example (6) we come across the exact same issues in which neither lava nor piatti are the head of the compound for both the semantic and morphological reasons we discussed. Thus, we theorize that the compounds get their category and features from a head on the outside of the compound. This is a phenomenon known as the silent –er affix which can also be observed in other languages such as French. With this theory in mind, we get the following trees for apriscatole and lavalpiatti to replace the previous two trees above.

(7)

(8)

This silent –er affix behaves just like the –er affix in English; it carries the meaning “a person or thing who X’s” and it selects verbs to attach to and changes them into nouns. This explains how these compounds get their corresponding categories which are different from those of their roots. This silent –er affix becomes the head of the compound even though it is on the outside of the compound and although there is no head on the inside of the compound we still include the LHR as a default rule to carry the verb category upwords so that the –er affix can select and attach to a verb. Interestingly, we have noticed that both apriscatole and lavapiatti contain plural suffixes but the compounds can be both singular or plural. However, we are unsure how the plural suffix attaches to the affix, whether it attaches within the compound or outside of the compound. Because of this uncertainty we have not included the plural suffix in the trees and therefore there is missing a sister node somewhere although we are uncertain of where exactly.

Interesting Exceptions

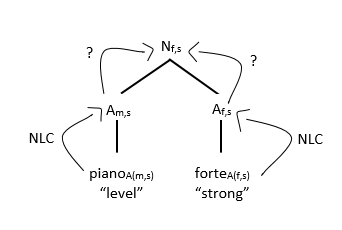

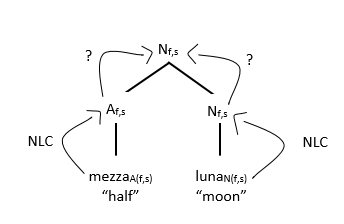

Although our theories of Italian compounding explain many of the Italian compounds we have found we have also come across a few exceptions. These can be seen in example (9) pianoforte “piano” and (10) mezzaluna “half moon” below.

(9)

(10)

In example (9), both of the roots are adjectives but the compound as a whole is a noun. We are unsure how the noun category gets to the topmost node. One might hypothesize that there is a silent –er affix that also attaches to the compound here and makes it a noun but this can’t be the case as the –er affix only attaches to verbs. Similarly, example (10) has a left most root that is an adjective and a right most root that is a noun and the whole compound is a noun. This tree seems to suggest a case where a right-hand head rule may apply but with all of our research it is the only compound like this that we were able to find. Thus, more research would need to be done to explain cases such as these.

Conclusion

In conclusion, compounding definitely is very interesting to analyse in Italian morphology, given all of the different types of compounds that can be found in the language as well as the presence of the silent affix. However, more research is needed to better explain those Italian compounds that seem to be exceptions to the Italian compounding rules we have found.

References

Baker, M. C. and Bobaljik, J. D. (2002-2008). Chapter 3: “Compounding”. Rutgers and Mcgill.

“Italian Language”. Wikepedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_language.

San Filippo, M. (2016, December 17). “Forming Italian Compound Nouns.” ThoughtsCo. Retrieved from https://www.thoughtco.com/forming-italian-compound-nouns-2011606.

Travis, L. (Fall 2017) Class Slides: “Compounds”. Mcgill University. Slide 14-